Assessment is a topic often discussed in the many corners of the education world. Whether a child is enrolled in their local public school, an independent school, or is homeschooled, assessment will most likely play a role in that experience. To what extent it plays varies greatly, however, as does the prevalence of the different styles of assessment. With NAPLAN happening this week, we thought it was a good time to explore assessment in a Montessori setting.

Parents often have strong feelings about assessment, although their perspectives can vary greatly. Many are frustrated by the now-common high-stakes testing, the amount of time testing can take, and the young age at which formal assessments are now taking place. Others, with their child’s future firmly in the forefront of their mind, want to be sure there are assessments in place that will clearly identify their child’s strengths and weaknesses.

So why do we assess in the first place?

One important reason is to measure learning. Another is to (theoretically) encourage success.

We pose the following questions: How do we define success? What exactly is it that we value and want to encourage in our children? What kinds of time restraints should (or should not) be placed on children as they progress through the learning of various skills? Should learning be measured in a standardised and linear fashion?

The following types of assessment are regularly used in educational settings. We describe each one and look at how Montessori does (or does not) implement them.

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment can be classified by the following characteristics:

- It is generally done while the student is learning.

- It is either unobtrusive or minimally intrusive to student work.

- It is almost never graded.

- It allows teachers to shift their approach mid-lesson.

Summative Assessment

Summative assessment is quite different. It’s a test or an exam. It can be classified by these characteristics:

- It is done periodically to determine whether a student has mastered a skill/skill.

- Learning and instruction must stop and time must be set aside to administer assessment.

- Grades/scores are typically assigned.

- It serves to categorise students and define success/failure.

Just by reading through the characteristics you will likely draw your own conclusions as to which style is more helpful to both students and teachers.

Keep in mind that in Montessori schools, we believe the following basic principles:

1. Learning is not linear.

There are general developmental phases that children pass through, but we recognise that there is great variation among individuals. This variation is honoured and even celebrated. One of the greatest benefits of our three year cycles is that teachers have that much time to work with children and guide them toward various goals. Most teachers understand that a child may progress in reading for 6 months while their mathematics skills plateau, but that could easily switch in time. Not feeling the pressure of having a child for one year only allows us to support natural learning and growth, and to let children learn according to more normal timelines.

2. Children do not need to compete with one another.

We believe that children do not need to compete with one another, but rather draw on internal motivation to better themselves. Grades lead to such competition. All people have areas of strength and areas that we may have to work harder at. When children begin comparing themselves to one another, many will be left with completely unnecessary feelings of inadequacy. Such dips in self-confidence can take a serious toll on children in the long term.

3. We do not utilise external rewards.

To expand upon point number three, we do not utilise external rewards. We find them ineffective and would rather guide children toward trusting their own process. There is significant scientific research that backs this approach. More on that here:

4. We provide learning materials that allow children to assess themselves.

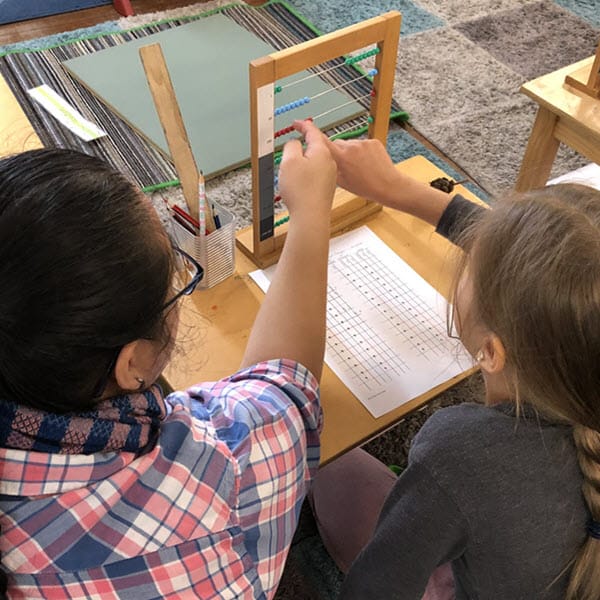

Most Montessori materials are autodidactic, that is the children learn the skill just from using them. If there is a series of different sized pegs with corresponding holes to place them in, there is only one way to complete the activity correctly. When a child is working independently with such a material and the last peg does not fit into the last remaining hole, they know a mistake has been made along the way and they can work toward correcting it.

5. Scientific observation is the most effective method.

Scientific observation is the most effective method for teachers to learn about students’ understanding. Dr. Montessori based her entire set of teaching methods on what she had observed about children’s learning over a span of 40+ years. Her constant observations allowed her to make changes in the environment and her approach. We believe this form of assessment to be the most effective tool we have. Montessori educators observe the children to determine what changes need to be made in their instruction in order to meet academic goals, but we also observe how the environment serves the children so that it can act as another tool to support learning.

What it boils down to is that we hope to teach children how to learn, not how to get a good grade. We want them to be enamoured with the world and find a deep and authentic desire to learn as much as they can about it. We do not wish to interrupt their learning with tests that do not actually serve them in the long run; rather we believe that the summative assessment approach of highly trained and skilled educators is the best way to support growth.